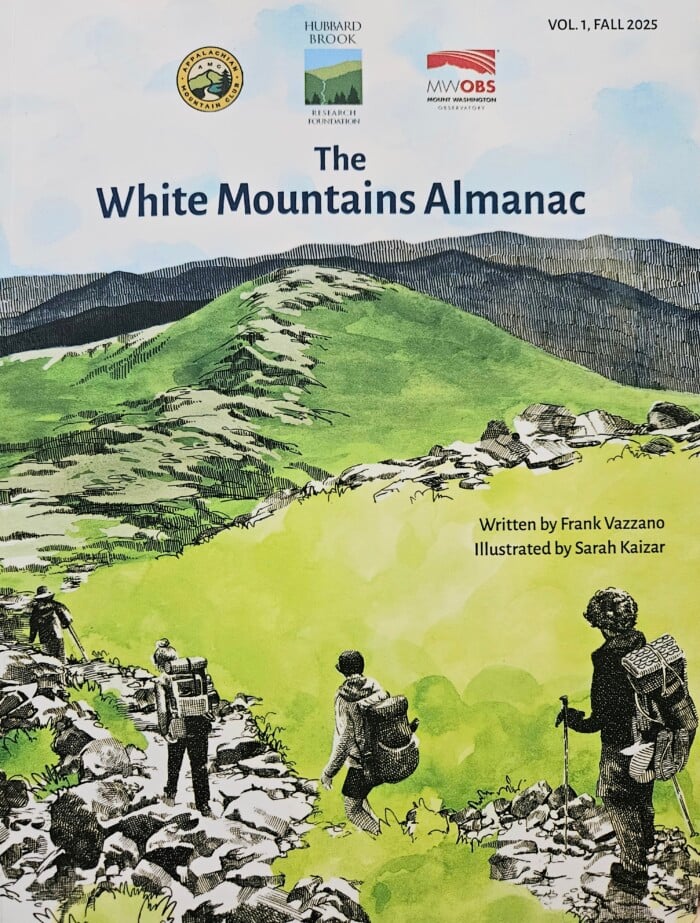

People come from near and far to recreate in the White Mountains. They’re an iconic landscape and an indelible aspect of our state’s identity, which is what makes the publication of the White Mountains Almanac feel like a moment worth celebrating.

Produced by the collaborative efforts of the Mount Washington Observatory, the Appalachian Mountain Club, and the Hubbard Brook Research Foundation, this illustrated work explores ecological and climatological changes across the White Mountains region, bringing together weather data, seasonal patterns and scientific insight about one of the most powerful mountain environments in the world.

The White Mountains Almanac explores ecological and climatological changes across the region. It was produced by the Mount Washington Observatory, the Appalachian Mountain Club and the Hubbard Brook Research Foundation.

The almanac, which will be published annually, was authored by Frank Vazzano, an intern hailing from Colorado who spent five months immersed in the White Mountains.

“From the vast expanse of wilderness, to the unique flora and fauna, and the warm inviting communities that call these mountains home,” Vazzano writes in the almanac’s preface, “it is clear to me that the White Mountains must be preserved, protected, and researched so future generations can continue to enjoy their gifts.”

Perhaps most notable is the long-term regional data monitoring that informs the publication. The almanac features data sets from four collection sites: the Mount Washington Observatory at 6,280 feet elevation, the Pinkham Notch Visitor Center at 2,032 feet, both dating back to 1935, the Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest north of Plymouth, and a MWOBS cooperative weather station in North Conway, dating back to 1957.

“The almanac is really a celebration of that long-term monitoring,” said Anthea Lavallee, the executive director of the Hubbard Brook Research Foundation, in a recent press conference celebrating the almanac’s launch. “Long-term ecosystem monitoring gives us a superpower that we wouldn’t have otherwise. It gives us the ability to literally see across time.”

Organized by month, the almanac chronicles a journey through the seasons. The first chapter, titled “January: Winter Temperatures,” opens with a deep-dive into meteorological winter temperatures, concluding that all four locations have experienced significant increases in winter temperatures since the 1950s. At lower elevations, temps have increased by about 6℉ while mid to higher elevations have seen temps rise by about 5℉ since the 1950s.

“By February,” the next chapter opens, “winter has long established itself in the White Mountains.” Here, Vazzano builds on winter temperatures by analyzing the increasing frequency of thaw events and the hazardous implications of those events in the backcountry as well as on local infrastructure.

Titled “March: Winter Recreation Days,” the third chapter offers a more complex deep-dive by investigating the impact of temperature and thaw events on “ideal winter recreation days,” a metric Vazzano designed involving snow depth, daily snowfall, and daily average temperature measurements.

“This is one of my favorite months “because it connects the data to what we do out in the environment,” said Jay Broccolo, director of weather observations at the Mount Washington Observatory. “This is how it engages the community, but then also infers what we’re all experiencing or what we think we’re experiencing.”

The portrait of the region’s character continues into the summer season: alpine growing days for certain flora, severe weather events, and a chapter on ideal summer recreation days, the August equivalent to March.

“This is the baseline information,” said AMC Senior Scientist Georgia Murray. “Climate is what you expect. Weather is what you get.”

Among the charts, graphs and text, the almanac features illustrations by Sarah Kaizar, a Philadelphia-based illustrator who has published two books, one work about long-distance backpacking culture on the Appalachian trail and a second collection of stories on North American bird conservation.

Flipping through the almanac’s pages, readers will recognize the White Mountain National Forest avalanche advisory sign at Hermit Lake, the awning covered in snow; a skier navigating backcountry terrain on Mount Washington, the winter sky captured in purple and blue watercolors; or common woodland plant varieties, the rich petals of red trillium or the delicate, drooping blooms of the ephemeral yellow trout lily. The illustrations, a beautiful visual testament to the publication, assist in communicating complex scientific data in a way that is both accessible and familiar.

The intent is that the almanac will be used to educate visitors to act more sustainably, provide businesses with data to inform their work in tourism and conservation, and give researchers a platform upon which to expand and provide insight at the legislative level.

“I think a lot about New Hampshire as this geographically small, but rather mighty state with an outsized impact on the wider world,” Lavallee said. “It is not an exaggeration to say that in New Hampshire, scientific insights and long-term ecosystem monitoring have influenced landmark bipartisan environmental policy that literally protects the air we’re breathing today and the water that I was just drinking a second ago and the iconic landscape here that we care so much about.”

A limited number of printed almanacs will be available at locations around the state, such as AMC huts and tourism centers. Digital copies of the almanac are also available on the partner websites, such as mountwashington.org

For more information, visit outdoors.org.