The New Hampshire Supreme Court once again says the state has failed to fulfill its constitutional duty to fund an adequate education as ordered by the justices in the foundational Claremont litigation nearly three decades ago.

The justices quashed the state’s appeal of Superior Court Judge David Ruoff’s ruling in favor of the Con Val School District that the $4,182 per student provided by the state is “facially unconstitutional” and deemed his calculation of $7,356.01 a “conservative approach” and “eminently reasonable.” On the other hand, the court reversed Ruoff’s order that the state “immediately” begin paying for base adequacy at the stipulated rate.

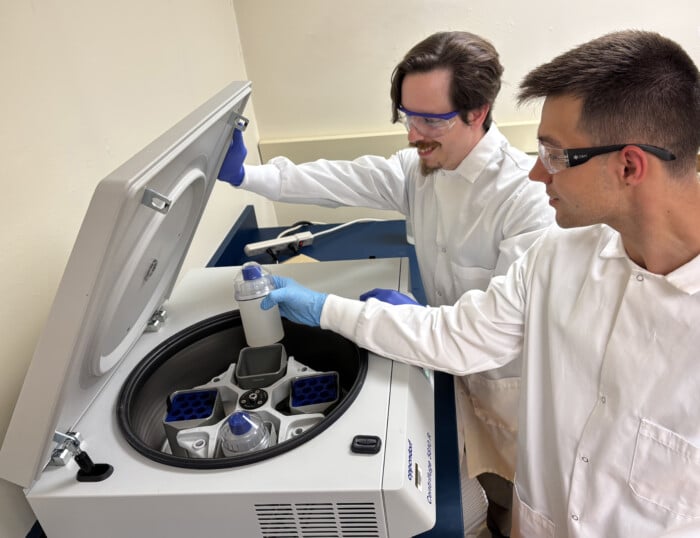

Rockingham County Superior Court Judge David Ruoff has been presiding over the suit brought by ConVal and 10 other New Hampshire school districts. (Michael Moore/The Keene Sentinel)

Senior Associate Justice James Basset wrote the opinion and was joined by retired justices Tina Nadeau and Gillian Abramson in the majority while Associate Justices Patrick Donovan and Melissa Countway dissented while all save Nadeau and Abramson shrank from ordering the funding be adjusted immediately.

“In sum,” Bassett wrote, “we conclude that, in imposing the extraordinary directive for immediate payment, the trial court failed to accord sufficient weight to separation of powers concerns viewed in the context of the history of the narrow legal issue presented, and the court thereby unsustainably exercised its discretion.”

The ConVal litigatio,n began in 2019, reached a stalemate in Superior Court then was appealed to the Supreme Court by both parties. The justices found the case posed a “mixed question of law and facts” disputed by the parties and remanded the case back to Superior Court, giving Ruoff the challenging task of pinning a price tag on a constitutionally adequate education.

Bassett opened his opinion by reaffirming the Claremont orders of 1993 and 1997, which held that the NH constitution imposes a duty on the state to provide a “constitutionally adequate education” to every child and to ensure it is adequately funded with constitutional taxes. “At no time,” he added, “has this court deviated from the holdings in Claremont I and Claremont II or their constitutional underpinnings.”

In its appeal the state offered two major arguments. First, the state sought cover behind the separation of powers doctrine, asserting that setting educational policy and determining sufficient funding are the sole prerogatives of the legislative and executive branches of government, over which the judiciary has no authority. “We are unpersuaded,” Bassett wrote dismissively, citing a prior opinion of the court that ‘“it is the judiciary’s constitutional duty to review whether laws passed by the legislature are constitutional.”

The state also contended that the cost of an adequate education was confined to cost of providing instruction in the eleven subject areas listed in the statute defining its content. Bassett noted that it was appropriate to reach beyond the narrow bounds of the statute when reckoning the cost of delivering an adequate education to include the costs of operating and maintaining facilities, purchasing materials and equipment, counseling and transporting students, paying salaries and benefits and so on.

By doing so, Ruoff was following the directive given him by the court. On the other hand, Bassett acknowledged, as Ruoff observed and the record confirmed, that “the State did not offer affirmative evidence justifying the sufficiency of the current funding level.”

One of the state’s three expert witnesses, a business administrator from one of the 20 school districts to join the suit, testified that he was charged with preparing a budget funded solely by the funds the state provides, but abandoned the task when he found he could not build a workable budget with the money available to him. A second expert witness conceded he could not describe the content or tally the cost of an adequate education and the third said it is “not a feasible exercise.”

In their separate opinion Nadeau and Abramson agree with almost all of the lead opinion, but object to reversing the immediate payment directive by. addressing the question of the separation of powers directly. They write while most rights are negative rights in the sense that they restrict the authority of government. In this case the role of the court is “to police the outer limits of government power.” But, the right to an adequate education is a positive right that “requires the State to take affirmative steps to meet its constitutional obligations” or as a prior opinion put it “Positive constitutional rights doing not restrain government action; they require it.”

“The court is the final arbiter of state constitutional disputes,” Nadeau and Abramson stress, “and the judiciary has a responsibility to ensure that constitutional rights not be hollowed out.” They note while “the constitutional right of a state funded adequate education has not been fully funded for decades” and argue the time has come for a judicial remedy. “In short,” they write, “we do not find that knowingly enacting a statute that woefully underfunds education shows good faith action on behalf of the Legislature such that the judiciary is precluded from exercising its duty to provide a meaningful remedy.”

Recalling that in 1998 the Supreme Court observed that the delay in fashioning a constitutional system to fund public schools was “inexcusable,” Nadeau and Abramson concluded that if the delay was inexcusable then “it is beyond comprehension today.”

The court’s decision has set the scene for the second challenge to the school funding system Mounted by Steven Rand, a Plymouth business owner joined by other property taxpayers, which has been tried before Judge Ruoff in Superior Court, who has yet to issue his ruling.

Since the Rand case also charges that the state has failed to fund its obligation to fund an adequate education, with the court’s decision in ConVal it has cleared, the first hurdle. But, the Rand suit goes further to claim because the state is shirking its duty, local property taxpayers bear the lion’s share of the burden of funding public schools with property taxes, contrary the Supreme Court’s holding in the Claremont litigation.

Then the justices held that because local property taxes serve to fulfill the state’s obligation to fund public schools, they are, in fact state taxes and therefore must be “equal in valuation and uniform in rate” throughout the state, which of course they are not. In other words, unlike the ConVal suit, which confined itself to the cost of an adequate education, the Rand suit challenges both the insufficiency of state funding for public schools and the legitimacy of the local property taxes levied to compensate for it.