Superior Court Judge David Ruoff has once again ruled that the state has shirked its duty to fund an adequate education and this time further held that local school property taxes, which vary in rate from one municipality to another, are themselves unconstitutional.

The decision in the suit brought by Steven Rand and other property taxpayers falls on the heels of the ruling by New Hampshire Supreme Court in July that quashed the state’s appeal of Ruoff’s order in the suit led by the ConVal School District and joined by 25 other districts.

Then the justices upheld Ruoff’s opinion that the $4,182 per pupil provided by the state is “facially unconstitutional” and deemed his calculation of $7,356.01 “eminently reasonable.” However, the court reversed Ruoff’s order that the State “immediately” begin paying for base adequacy at the stipulated rate.

The Rand suit, argued by attorneys Andru Volinsky and John Tobin, both veterans of the Claremont litigation of 1990s, and Natalie LaFlamme reaches well beyond the ConVal suit. The Rand plaintiffs charge that the paucity of state funding places the overwhelming burden of funding public schools on local property taxpayers, contrary to the foundational orders of the state Supreme Court in the Claremont decisions of the 1990s, with which the state has yet to comply.

Unlike the ConVal suit, which only sought an increase in state aid per pupil, the Rand suit seeks to reaffirm and enforce the Claremont decisions by addressing both the inequitable property tax burdens born by taxpayers and the inequitable educational opportunities afforded to school children.

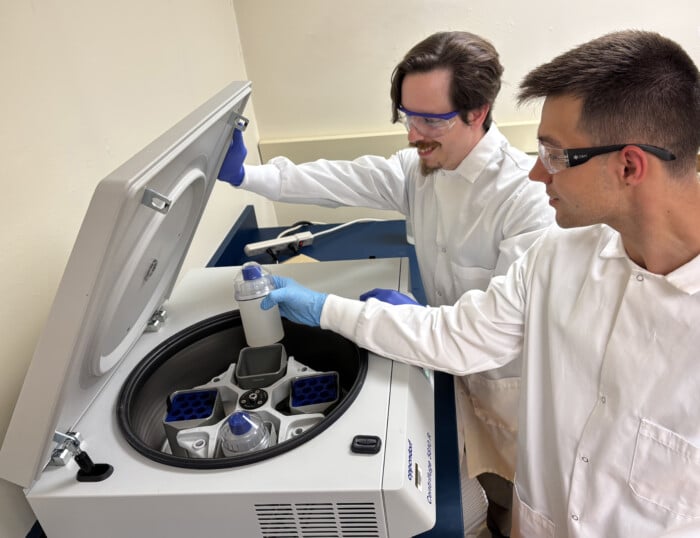

A ConVal school bus. The state’s education funding formula is the subject of an ongoing legal battle. (File/Ben Conant/Concord Monitor)

In 1993, the court held in Claremont I that the state constitution places an “unequivocal legal duty” on the state “to provide a constitutionally adequate education to every educable child” as “a fundamental right” and “to guarantee adequate funding.” Four years later the court ruled that the state must define the content of an adequate education, determine its cost and fund it with constitutional taxes “equal in valuation and uniform in rate throughout the state.”

“There is nothing fair or just about taxing a home or other real estate in one town at four times the rate that a similar property is taxed in another town to fulfill the same purpose of meeting the state’s educational duty,” the justices declared, referring to the tax scheme as “fiscal mischief.”

At the same time, the court drew a parallel between disproportionate property taxation and disproportionate educational opportunities arising from the disparities in property wealth among municipalities. “Imposing dissimilar and unreasonable tax burdens on the school districts creates serious impediments to the state’s constitutional charge to provide an adequate education for its public school students,” the court order read.

At trial the Rand plaintiffs argued that state funding falls far short of the actual cost of providing an adequate education. John Freeman, who served as principal and superintendent in half-a-dozen school districts, developed a “mock budget” by tailoring Pittsfield’s “efficient, threadbare” budget of $10 million to the $2.7 million the state provided the district. He concluded that even doubling the state share would fail to fund a constitutionally adequate education.

Freeman stressed the challenge of recruiting and retaining teachers with average salaries of $41,717 compared to the state average $59,198, noting that one year all the elementary school teachers left at once. Apart from teachers, he said a school cannot function without the means to provide administrative, transportation, custodial, nursing and other ancillary services.

Likewise, Corinne Cascadden, a former principal and superintendent in Berlin, echoed Freeman’s testimony. She told the court that in 2020 the district “nickeled and dimed” to craft a “bare bones” school budget of $18 million, to which the state contributed only $5.6 million, leaving the balance of $12 million to local property taxpayers.

While the ConVal suit confined itself to the per pupil cost of an adequate education, the Rand suit also addressed the differential aid for students qualified for free and reduced priced lunch, learning English language and particularly those entitled to Special Education Services. Special Education students currently qualify for $2,100 in addition to base adequacy of $4,182 while in 2023-2024 the average cost of serving these students was $49,812. Local property taxes accounted for 83 percent of special education revenues.

In framing his opinion Ruoff leaned heavily on the testimony of Freeman and Cascadden by treating Pittsfield and Berlin as “bellwether” districts on the presumption that if state funding is not sufficient to ensure an adequate education there, then it is not sufficient in any other school district. Both Freeman and Cascadden demonstrated that with only state and federal funding neither Pittsfield nor Berlin could provide a constitutionally adequate education without drawing revenue from local property taxpayers.

Ruoff noted that “the state offered no affirmative evidence justifying the sufficiency of current adequacy funding and special education differentiated aid funding levels.” Instead, the state contended that apart from “adequacy funding” the state provided other forms of funding to schools, including building aid and earmarked grants. Ruoff considered the impact of such funding minimal and neither assured from year to year nor uniform throughout the state.

The state also presented several expert witnesses. Jay Greene of the Heritage Foundation criticized Freeman’s methodology and conclusions while suggesting New Hampshire model itself “after education systems in developing countries” and discounting the value of experienced teachers.

“In summary,” Ruoff wrote, “the plaintiffs have proven a clear and substantial conflict between the costs necessary to meet Constitutional Adequacy and current Adequacy Funding and special education differential aid and funding levels in all, or virtually all, of New Hampshire’s school districts.” The effect,” he explained is “to convert a portion of local school taxes into a State tax that is assessed at varying rates throughout the State in violation of Part II, Article 5” of the Constitution.

Ruoff acknowledged the role of the Legislature in setting educational policy while asserting the responsibility of the judiciary “to ensure that constitutional rights not be hollowed out.” He noted that the school funding scheme has “run afoul of not one but two provisions of our State Constitution — Part ii, Article 5 and Part II, Article 83. “The Court,” he continued, is now called to enforce these constitutional provisions without regard to the legislature’s compliance with those provisions would be cumbersome or otherwise challenging.”

The Rand plaintiffs asked the court to enjoin the state from continuing to operate under the current school funding plan April 1, 2026. Ruoff denied the request, anticipating the state will appeal his decision. However, he added that should the plaintiffs come to believe that the “Legislature is not acting diligently in this regard,” they may seek injunctive relief.