United Therapeutics found the Millyard the perfect setting to help meet its core mission: that no one should ever die waiting for an organ.

EwingCole principal Michael Ramus shared the company’s decision to open a corporate research and development facility in Manchester during a Sept. 16 panel talk at ACCESS 2025 titled “Reimagining Spaces: Adaptive Reuse for Community Growth.”

United Therapeutics, a biotechnology company based in Silver Spring, Maryland, is focused on manufacturing organs to treat chronic diseases. One step toward the company’s goal was having enough room for labs, research areas and sterile rooms to conduct testing, Ramus told attendees.

Ramus, who specializes in health care and science/technology facility design at the architecture and engineering firm EwingCole, collaborated with United Therapeutics to develop the 98,000-square-foot research and development center at 100 Commercial St., formerly known as the Seal Tanning Building.

United Therapeutics, founded in 1996, is a public benefit corporation and a founding member of the Advanced Regenerative Manufacturing Institute, a Department of Defense Manufacturing Innovation Institute that is fast-tracking the development of biotechnologies and biomanufacturing. The project at 100 Commercial Street was completed in 2023.

Researchers there are developing 3D-printed frameworks, or “scaffolds,” upon which stem cells can be grown and eventually produce human lungs for possible transplant.

Ramus made his presentation during the annual economic growth conference that was hosted by the Greater Manchester Chamber of Commerce and presented by Bellwether Community Credit Union at the DoubleTree by Hilton Hotel in Manchester. His presentation was sponsored by the volunteer-led Manchester Development Corp.

Ramus explained how EwingCole’s forward-facing design aesthetic was a match for the biotech company’s vision.

“United Therapeutics is very big on design. They kind of let us do more than we might get away with (compared with) some clients,” Ramus said.

The design team focused on the south section of the first and second floors and the entire third and fourth floors. The building contains labs, corporate offices and additional amenities, according to EwingCole.

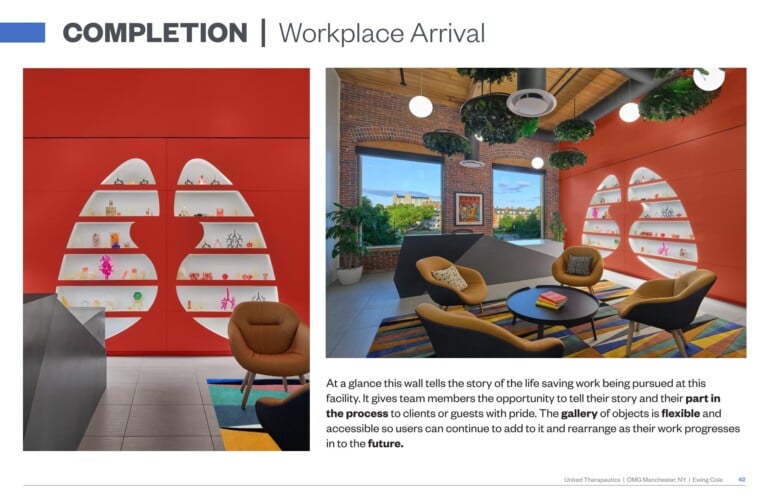

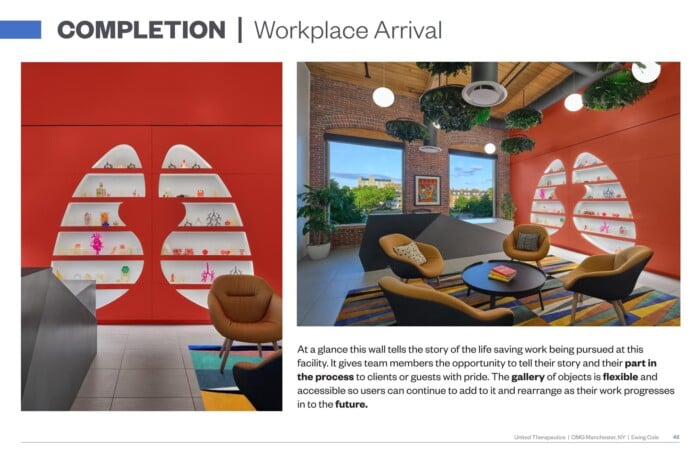

EwingCole sought to include narratives to the project, including display shelves that are in the shape of United Therapeutics’ logo. (Photo by Halkin | Mason Photography)

The first three floors include lab space for processes like cell analytics and production and tissue-culture preproduction and printing, while the fourth floor includes conference rooms, work stations and a café, according to previous news reports.

For this project, Ramus and EwingCole collaborated with a local historic group to preserve as much material as possible from the original building, from its historical light fixtures and old gears to the color of paint on the walls and ceiling height.

“(The local historic group) really does play an important part in preserving our cultural heritage of the city,” Ramus said.

According to one slide obtained by EwingCole, their team “balanced the need for durability and cleanability” in lab settings by using materials like zero- to low-VOC products that aim to cut back on carbon emissions, and eliminating or limiting stain repellents and flame-retardant treatments. They also prioritized using Red List-free products, which are deemed to be free of harmful chemicals.

“There is a truly sustainable story behind that as well. So you’re preserving history, you’re protecting the environment. There’s definitely value in that,” Ramus said.

United Therapeutics requested the creation of “clean rooms,” sterilization lab spaces where staff can perform research.

EwingCole’s vision for United Therapeutics’ lab spaces included adding color accents on the floor to define circulation versus work zones. (Photo by Halkin | Mason Photography)

“So how do you bring in this high-tech science and technology research development (space)? We need to create spaces that are sanitary, where they have these sorts of chambers. It doesn’t need to be necessarily purely sterile, but it still needs to be a clean environment. So we had to create these anterooms on all the floors,” Ramus said.

The anterooms were previously open spaces; now, staff use them to change clothing before entering the more sterile lab environment.

”If you were just standing here, you’d have no clue that you were in an 1800 mill building,” Ramus told the room.

Beyond the sterile lab spaces, some of the original mill equipment and infrastructure were also incorporated into the design. The perimeter masonry walls and timber ceiling with gears and pulleys were preserved. One gear was turned over to become a base for tables, while another large gear greets visitors in the building’s lobby.

Contemporary conservation

“You can preserve history and you can still be contemporary,” Ramus told the group.

The building now houses a fitness center and room for fitness classes, and installed flooring compliant with the Americans with Disabilities Act. Fractional tiles on the ceiling helped lower the noise level in the building, while keeping as much of the exposed ceiling as they could, though the labs were one place where exposed ceilings weren’t ideal.

EwingCole’s project included a fitness center, a space for fitness classes, and shower rooms. (Photo by Halkin | Mason Photography)

“The labs had to have ceilings in them for that stability, but anywhere else, we tried to keep those ceilings open and exposed. We had to do all this while the building is still operational, at least in one portion,” Ramus added.

All of the aspects that EwingCole incorporated into the design created “a space that’s truly livable and comfortable, still respecting the architecture. It’s quite a bit of square footage,” Ramus said.

Another way they kept the original look of the building was by preserving exposed ductwork, but only to a certain extent, and sometimes at cost.

“We don’t want to necessarily go too industrial, so we’re wrapping it and then painting it, so there’s extra cost to that,” Ramus said.

Updating HVAC services required giant “shafts” that went down through the middle of the building. To stay within building codes, they created a fire-rated enclosure for the shafts and built a concrete, steel platform that supported the shaft.

The concept of carbon reduction and sustainability is a “big trend” in design today, Ramus says, adding that the best way to not release millions of cubic yards of carbon into the atmosphere is by using what’s already available.

“The best way to do that is to reuse a building, not tear it down and let it stand. That’s not going into a landfill. You’re not putting new steel up. You’re not putting excessive amounts of concrete in,” Ramus said.

Another project goal was to visually incorporate outside elements into the interior design, known as biophilic design. The industrial building, which sits alongside several similar structures on the Merrimack River, is a relic of Manchester’s past as a textile manufacturing center that relied on the river’s power to be successful.

“We tried to create a sort of river effect on all the floors, where we’re right against the Merrimack,” Ramus said. “We tried to bring in colors of nature. We really did try to bring the outside inside.”

Ramus stressed that using a low-key, transparent approach when collaborating with local organizations was optimal for all parties.

“Rather than us coming and pitching, ‘Oh, this is what we’re doing’ — and again, it’s historical — we were saying, ‘Look, this is what we’re proposing to do. What’s your feedback?’ If you come at it with that approach, it’s much less confrontational, and it makes my life easier.”

Ramus explained how he and EwingCole’s team drew inspiration from the building’s industrial past in the heart of Manchester’s textile mill historic district.

“We tried to preserve as much of that industrial culture as we could, and we worked really closely with the city,” he said. “We made two rounds of presentations to them to make sure that we were doing something that wasn’t going to create a negative impact on the culture of the Millyard. It really was a conversation.”

The project also included staff amenities including health and wellness areas, like a gym and a respite space, where staff can have direct views of the river.

The design by EwingCole included a wellness and prayer room that also allowed space for nursing mothers and meditation. (Photo by Halkin | Mason Photography)

“We’re trying to keep as much as that nature and historical aspect of the space,” Ramus said.

A green and blue color palette and preserved plant walls complement the building’s biophilic design, creating a “connection” to nature and the outside world.

“You use these green hues, and you end up with space like that, really embracing that historical environment,” Ramus said during the presentation.

MDC chair, Amy Chhom, who moderated Ramus’ panel, says this is the second year that the local organization has sponsored ACCESS as it aligns with MDC’s mission.

During her introduction, Chhom had listed several adaptive reuse projects spearheaded by the MDC and also mentioned examples by private developers.

Among them are 252 Willow St., a 110,000-square-foot mill in the redevelopment zone out of the traditional Millyard area — Chhom redeveloped the property in partnership with the Orbit Group.

The Rex, a performance venue that began as a printing press and later became a movie theater from the 1940s to the 1980s, was also undertaken by MDC.

A car dealership on Second Street that became a 17,000-square-foot medical office building was redeveloped by NH Eye Associates.

Another successful adaptive reuse project, redeveloped by Brady Sullivan Properties, is the six-story, 115,028-square-foot building at 1230 Elm St., which now contains 100 luxury apartments. Built in 1973, the site was a former commercial space housing businesses including Metropolitan Life Insurance and New England Telephone and Telegraph.

Chhom says projects like these, that focus on historic preservation, are also environmentally friendly, despite the fact that many old buildings like these have pre-existing environmental issues that would eventually need to be addressed.

But, Chhom reasoned, adaptive reuse projects maintain the aesthetic of a previous age but also keeps less trash out of landfills.

“If we took that building down, that’s tons and tons and tons of brick, and it’s a building that can never be really created in today’s day and age,” Chhom said.

She highlighted the gravity of Manchester’s transformation from a textile manufacturing center to a biotech hot spot through the overall value of adaptive reuse projects.

“What’s happening in the Millyard, with us now transforming (the area) from being an industrial technology to software technology, (to) now we’re into ‘growing organs’ technology, right? To be able to do what they’re doing in that mill today … could you imagine being a mill worker and someone told you, in 200 years, somebody’s going to be growing lungs in this building?” Chhom said.

(This story has been updated to reflect the correct address for a redevelopment project at 252 Willow St. and includes clarifications regarding which adaptive reuse projects were undertaken by Manchester Development Corp.)