CairnSurgical aims to make breast cancer surgery more precise

Lebanon company’s technology helps surgeons pinpoint size, shape of tumors

Diane Uzarski, dean and professor of practice at the Jean School, wrote an op-ed about the nurse staffing crisis in NH. (Photo by Jodie Andruskevich)

Seeing nurses care for people with dignity and respect across language barriers inspired Samuel Assantha of Manchester to join the profession.

But Assantha also wants to help the people he knows and loves.

Assantha, who moved to Manchester from the Democratic Republic of Congo about 10 years ago, says he’s lost many friends and family members who lacked access to good health care. His uncle, a nurse, helped Assantha’s parents in the U.S., and taught him the importance of caring for others.

“Acting as an advocate for my family has helped me develop a passion for medicine,” he says.

When he graduates this year with a nursing degree from the Jean School of Nursing & Health Sciences at Saint Anselm College, he’ll get the chance to help many more.

So will Julia Marzolini of Hudson, who is seeking a Bachelor of Science in Nursing (BSN) degree at the Jean School. Marzolini, who expects to graduate in May as the fourth-generation nurse in her family, plans to start her career at Southern New Hampshire Medical Center in Nashua, where she’s currently a licensed nursing assistant.

“I’ve been inspired by a strong legacy of service and caregiving,” Marzolini says. “I am committed to building my foundational years of practice there while continuing to grow as a nurse.”

Assantha knows it’s a challenge, but sees the value in being a nurse.

Samuel Assantha of Manchester, seen here at St. Anselm College’s Savard Welcome Center, is a senior seeking a bachelor’s degree in nursing from the Jean School. (Photo by Jodie Andruskevich)

“Hospitals are vulnerable places for people, and as a nurse-to-be, I strive to build therapeutic, trusting relationships with my patients and to support them through difficult times,” Assantha says.

Both will join a growing workforce of recent grads across New Hampshire preparing to enter a field in dire need of nurses. But as New Hampshire health educators sound the alarm about the staffing crisis, the health care community is making strides to lessen its effects.

As baby boomers age, the nationwide shortage of registered nurses will increase, according to the American Association of Colleges of Nursing. Factors include rising stress levels, compounded by the pandemic, increased job dissatisfaction and burnout. The need for higher pay, an already aging nurse workforce and an interest in a better work-life balance have also exacerbated the crisis.

The shortage here is so profound that, in September, Diane Uzarski, dean of the Jean School of Nursing and Health Sciences at Saint Anselm College in Manchester, wrote an op-ed titled “Our Nursing Shortage Hurts Patients. Here’s How New Hampshire is Fighting Back.”

“It’s a crisis that touches every corner of the way we stay healthy,” she writes.

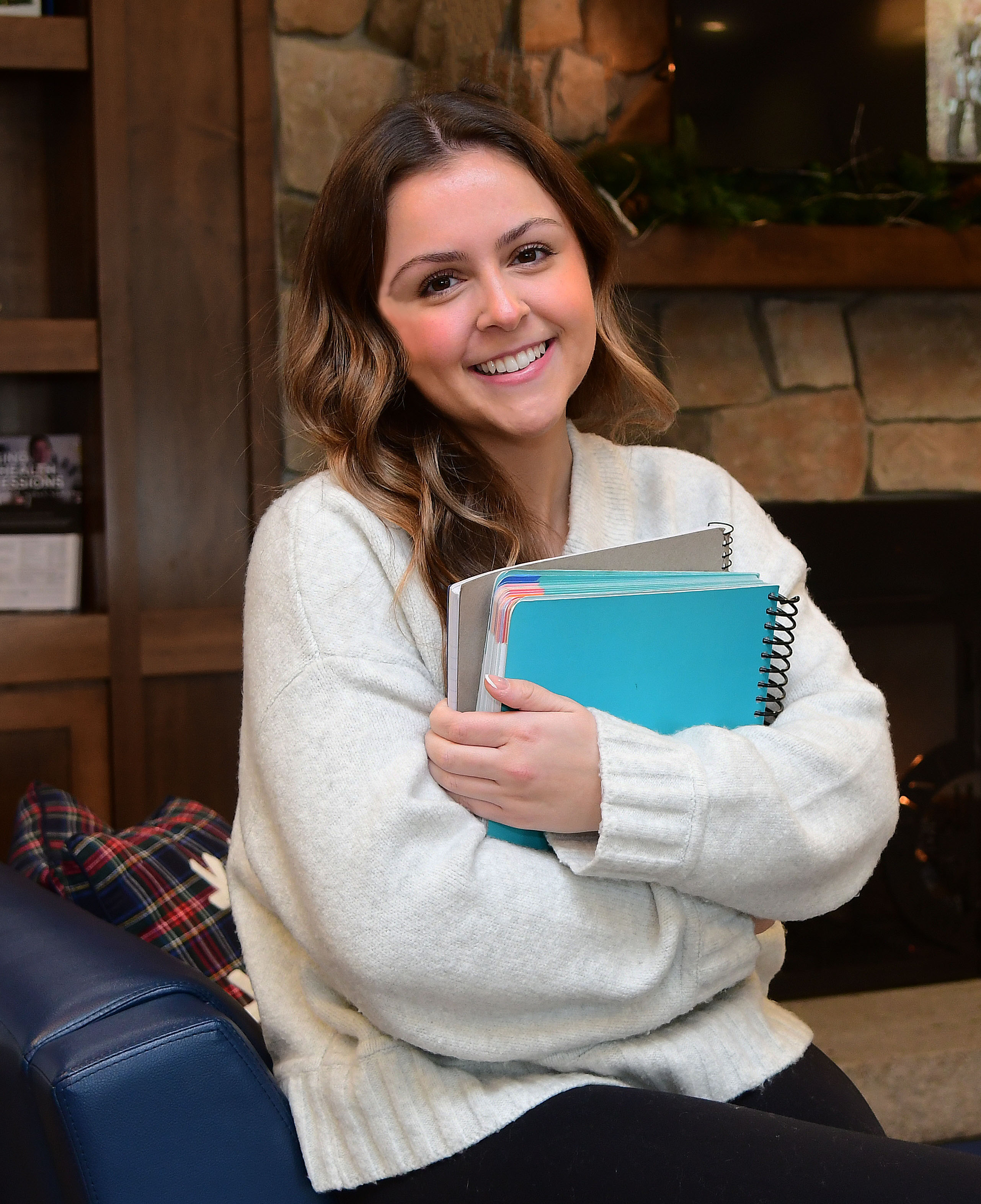

Julia Marzolini of Hudson expects to graduate in May with a Bachelor of Science in Nursing (BSN) degree from the Jean School of Nursing & Health Sciences at Saint Anselm College in Goffstown. Marzolini would be the fourth-generation nurse in her family. (Photo by Jodie Andruskevich)

Her column cites a New Hampshire Department of Employment Security estimate that, through 2026, there will be more than 900 annual openings for registered nurses and nearly 1,200 openings for nursing assistants.

“I’m really committed to the nursing profession and to the growth, the future of our workforce, quite frankly, and the alarm bells are ringing,” Uzarski says.

Other statistics highlight Uzarski’s warning. The National Center for Health Workforce Analysis projects that, by 2030, for a projected supply of 2,280 licensed practical nurses in New Hampshire, 3,640 will still be needed.

A shortage of qualified nursing educators due to lower salaries, combined with rural hospitals’ struggle to pay competitive wages, adds to Uzarski’s concerns.

“The salaries in academia are less than what nurses can make. We work very hard to recruit faculty, support faculty, provide for their education and help them develop and help them stay,” Uzarski continues.

The nursing education infrastructure, such as simulation lab facilities, is also limited here.

“Our arms are tied about how many students we could admit because we need the right number, the faculty, we need the facilities, we need the clinical placements for students,” Uzarski says.

Martha Dodge, chief nursing executive and senior vice president of patient care services at the Elliot in Manchester, agrees that it’s a “crisis” situation, especially when the state contains one of the oldest populations in the nation. While New Hampshire is a desirable place to work, the lack of affordable housing, higher living expenses and student loans are keeping prospective nurses away, she says.

“Pretty much all of our out-of-state students who graduate from my New Hampshire nursing program leave the state and go back to where they came from and work there,” says Dodge, who also cites the state’s limited education infrastructure.

“Our ability to enroll students is sort of capped based on faculty and clinical site availability,” Dodge adds.

President of Rivier University in Nashua, Sister Paula Marie Buley, adds that the North Country is also facing hardships like housing shortages.

“There is a greater limitation on social services, educational services, cultural services (there),” Buley says.

Buley likens the nursing shortage to a “natural brain drain,” as students seek higher salaries in neighboring Massachusetts or work in academic research hospitals. Buley says Massachusetts rivals New Hampshire with a more comprehensive mandated paid maternity leave law.

“They graduate, they get their experience, they anticipate starting a family, and they go to Massachusetts, and they have paid leave,” Buley says.

From left, Workforce Development Specialist & Granite State PARTNERS Project Manager, Sarah Vlasich, BSN, RN, CMSRN; President and Chief Operating Officer, Elliot Health System, Dr. Greg Baxter; U.S. Sen. Jeanne Shaheen; U.S. Sen. Maggie Hassan; Chief Nursing Executive and Senior Vice President, Patient Care Services, Martha Dodge, RN, MS, RN, CENP, CPPS; Director of Workforce Development & Experience, Becky Marden, RN, MSN, CNML, CPC; Retention Specialist, Vanessa Rashid. (Courtesy of Elliot Health System)

Boosting nursing education

Health organizations here are working to alleviate the shortage. In 2022, Saint Anselm College President Joseph Favazza established a Presidential Commission on Nursing to revamp the school’s program to align with changing technologies. The result was the Jean School of Nursing, formally established in July 2023.

The $35 million, 45,000-square-foot facility in Grappone Hall, funded through private donations and $4.7 million in congressional funding via NH Sen. Jeanne Shaheen and NH Congressman Chris Pappas, is equipped with a simulation center and learning environments ranging from pediatrics to public health.

Uzarski also consulted with regional chief nursing officers to create a Master of Science in Nursing Leadership and Innovation degree (MSN).

“It’s a boots-on-the-ground, very practical master’s program that is responding to the needs of our area hospitals,” Uzarski says.

Like the Jean School, Rivier University has also revamped its simulation labs through grant funding.

“(We) have allowed our students to practice in the state-of-the-art setting, so they’re prepared to go out and hit the ground running when they graduate,” says Vice President for Academic Affairs and Dean of Nursing and Health Professions Paula Williams.

Though Rivier doesn’t receive state funding, Buley says the school is grateful for support from Shaheen and other delegates.

“(Her) congressionally directed funding allowed us to create, really, an intensive care teaching space for over a million dollars,” Buley says.

Another Rivier initiative is its Accelerated Bachelor of Science in Nursing program, a fast-track pathway for anyone with a non-nursing bachelor’s degree to prepare for the NCLEX-RN exam and graduate in 16 months.

According to Williams, students are often already working, are older and attend college part-time with families, so they’re more likely to stay here.

“They really bring a wealth of knowledge to the nursing program,” says Williams, who adds that the number of students in the accelerated program has nearly doubled.

“We had 50 of them this past fall, in 2025, and we expect to have about 100 in the fall of ‘26 join our nursing program,” Williams says.

Uzarski says the student population at the Jean School has risen as well, from 500 to 657 in two years.

“We have basically 25% of the college’s population within the Jean School,” Uzarski says.

Buley and Williams say there’s also been a push to bring in more diverse, underrepresented populations into the field through grants totaling about $11 million since 2014.

“Whether it’s economic, whether it’s rural communities, whether it’s underserved urban communities, (these) are designed to expand the nursing workforce to Americans, to non-native English speakers, to those who historically would remain as LPNs. (These grants) provide tuition, fee money, additional academic support and professional development for faculty,” Buley says.

In 2023, the Elliot Health System lead a $3 million, collaborative, statewide nursing expansion grant from the Department of Labor called Granite State P.A.R.T.N.E.R.S. (People Aligning Resources Towards Nursing Expansion and Retention Strategies).

The five-year grant, which ends in 2028, was open to residents 17 and older who attended secondary school and were unemployed, underemployed or incumbent.

The grant allowed funding for 300 nursing students.

Dodge says more than 800 people applied; all slots have been filled.

“So there’s not a lack of demand,” Dodge says. Successful applicants can receive career guidance, coaching services, educational opportunities and financial aid, including tuition scholarships. Applicants can work anywhere, in any nursing field, or leave the state to find a job.

“The grant is really to look at the underserved and to give them an opportunity. Access and funding to nursing is a big barrier for us in the state,” says Rebecca “Becky” Marden, director of workforce development and experience at the Elliot.

Participants also get $250 for tuition and nursing supplies and have received grocery cards or gas cards to pay down bills.

“Somebody’s electricity was going to be turned off.

Well, you can’t do your studying if you don’t have any electricity. Car repairs, tires, just things that get thrown at you that you don’t plan on, that really become a big barrier for somebody that doesn’t have the financial means to overcome it,” Marden says.

“A car payment, college loan payments and rent — they’re not able to afford all of that right out of school,” Dodge says.

Jean School junior Julianna Bowman of Acworth says she chose the school mostly for its high graduate success rates. (Photo by Jodie Andruskevich)

The roughly 40 NH grant partners collaborating with the Elliot include New Hampshire Nurses Association, Southern NH Health, Foundation for Healthy Communities, Manchester Community College, Franklin Pierce University and Catholic Medical Center.

“We have over 300 different community members that work with us across the state,” Dodge says.

Schools collaborating with the Elliot include UNH, Colby-Sawyer College, Rivier University, Merrimack College, Manchester Community College and Nashua Community College.

Dodge, who also collaborates with Uzarski, says schools communicate with health care centers about exceptional students seeking work. Applicants can work with a nurse to get firsthand knowledge.

“We get hundreds of applicants for every spring semester for seniors; we place as many as we can,” Dodge says.

She says it creates a good testing ground. “We get a lot of hires out of that. People (are) sort of testing us out. We’re testing them out. And if it’s a good fit, we offer roles. We also have a lot of nursing students who work here as licensed nursing assistants,” Dodge says.

“We have a tremendous commitment to nurse education in our state. Our schools are doing a wonderful job.

We partner together. I talk with deans of schools on a regular basis,” adds Uzarski.

Julianna Bowman of Acworth, a junior pursuing a BSN at the Jean School, isn’t worried about entering a short-staffed field, but is wary of increasing work demands.

“It gives me hope that there may be more open opportunities when I graduate. It does, however, make me nervous about maybe the demands that can come in an understaffed environment, while you are still trying to become acclimated as a new grad,” Bowman says.

Like Bowman, Marzolini, who’s working as an LNA, knows she’ll be making a difference.

“(It’s) an opportunity to contribute to positive change in nursing. My experience working as a licensed nursing assistant in a New Hampshire hospital has given me valuable insight. I have been fortunate to work on a well-staffed unit that prioritizes teamwork and professional growth.”